Can AI Simulate Human Social Networks? Testing LLM Agents Across Countries

An investigation into whether Large Language Models can reliably simulate human social behavior, revealing how language and cultural context impact AI-generated social networks.

Project role

Data Scientist

Key skills

Data Analysis

Machine Learning

LLM Integration

Timeframe

Sep 2024 - Jun 2025

The Big Picture

Imagine asking an AI to roleplay as a person from Spain. Would it form friendships the same way as when it roleplays as someone from Japan? This seemingly simple question has profound implications for the growing field of AI-powered social simulations.

Large Language Models (LLMs) like GPT-4 are increasingly being used to simulate human behavior in social science research12. Researchers use these AI “agents” to conduct virtual user studies, model social dynamics, and predict community behavior—all without the ethical complexities and costs of human participants. But how reliable are these simulations?

My research reveals a critical gap: LLMs generate networks that look structurally similar to real-world ones, but fail at the individual connection level. Additionally, the predicted network structure would vary significantly based on the language and cultural context of the prompt.

Why This Matters

Social simulation with AI agents is being used in political science, economics, and communication studies. If researchers trust these simulations to predict real human behavior, they need to know the limitations.

Previous research has shown that LLM-generated networks have similar overall structures (density, clustering) to human networks3. But does structural similarity mean the AI is actually predicting who would be friends with whom? Think of it this way: I could generate a random social network with 100 people where everyone has about 5 friends on average—that might have similar statistics to a real network, but it wouldn’t tell us anything meaningful about actual friendship patterns.

Other studies have raised concerns about biases. This is particularly concerning when LLM agents play minority roles, as it suggests that LLM values may align more closely with specific cultural groups45.

Research Questions

- Edge-level accuracy: When we ask LLM agents to predict friendships, how accurate are they at the individual connection level?

- Cross-cultural variation: Does the language of the prompt affect how LLMs simulate social behavior? Do these variations reflect real-world cultural differences?

Initially this project is my final report in HCI research course in UC Berkeley, I bring them to New York University afterwards

Literature review before starting the project

Testing Edge-Level Prediction Accuracy

I used the Indian Village Microfinance dataset6. It is a real social network data from 77 Indian villages that records who people borrow money from, ask for advice, etc.

Data Preprocessing

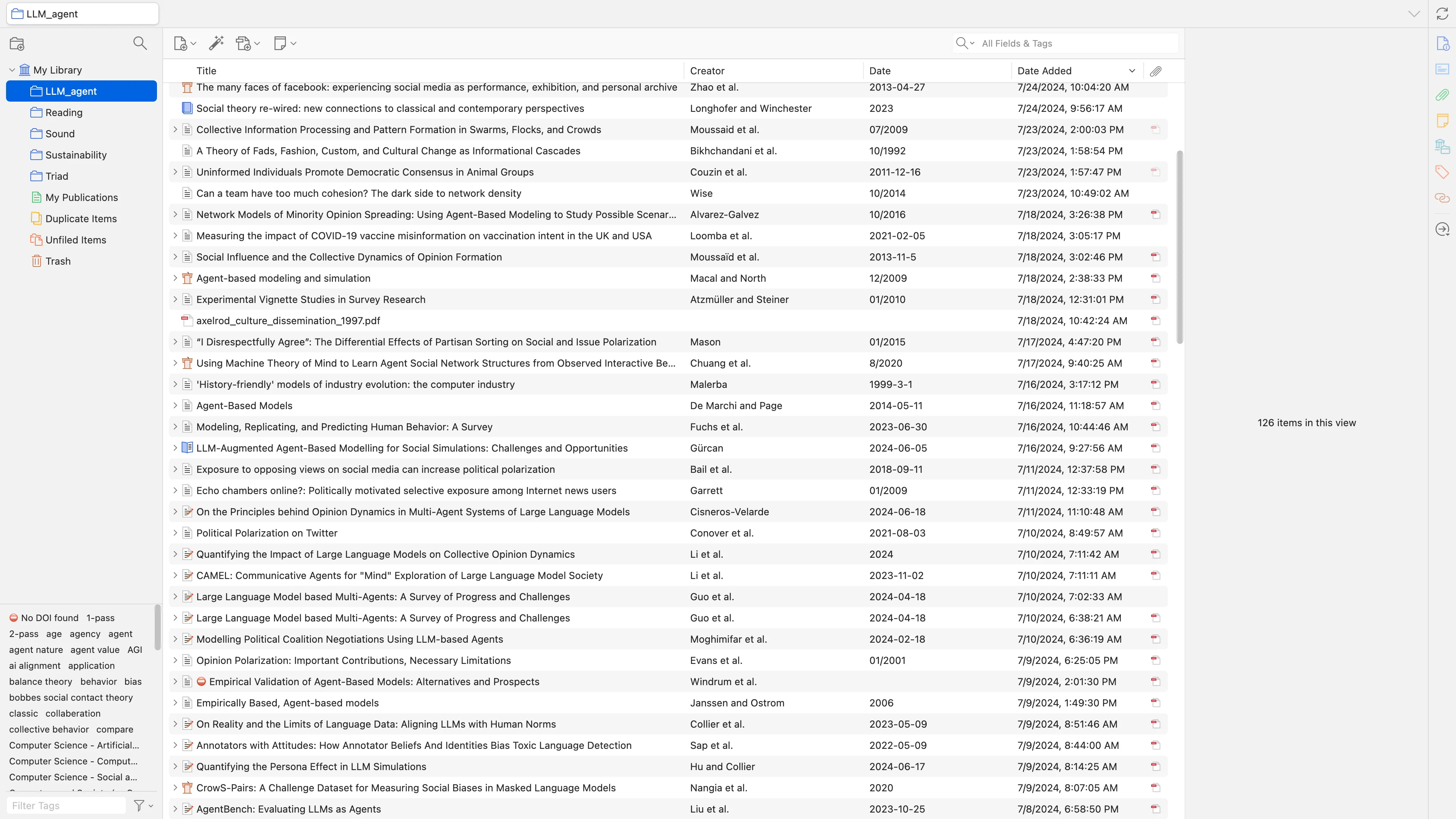

Our dataset is tie level, where each row represents a possible edge (friendship) between two people, along with their demographic attributes.

Find all possible pair of connections between any two villagers: (, )

Our data structure: edge-level representation of social networks

- Y= if the edge exist (0 or 1)

- X = demographic features of ,

Since the number of not exist edges is much more the existed edge, we applied balance method to prevent bias prediction.

In here we applied three balance method: SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique), ROSE (Random Over-Sampling Examples) and down sampled to handle class imbalance in friendship prediction.

SMOTE

Generate new edge (Y=1)

- Select a random edge

- Find the sample’s nearest KNN neighbors in feature space

- Generate a new edge between them

ROSE

Generate new edge (Y=1)

- Select a random edge

- Create a small noise according to data distribution

- Generate a new edge

Down Sampling

Drop non-existed edge (Y=0)

- Select a random non-existed edge

- Drop it

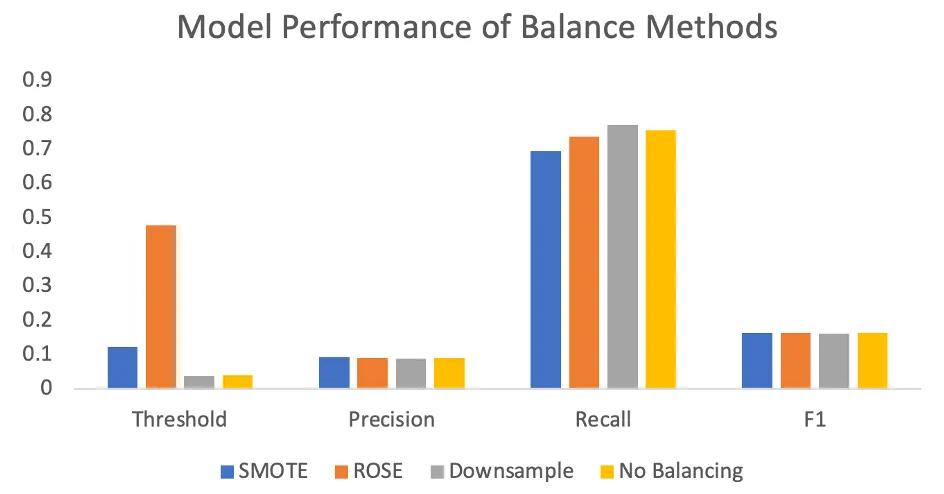

Comparison of different balancing methods on edge-level prediction performance

We trained Lasso Logistic Regression models on datasets processed with different class balancing methods to predict edge existence. Model performance was evaluated using precision, recall, and F1 score. All balancing methods yielded similar performance across these metrics, with SMOTE achieving the highest overall F1 score. We therefore selected the SMOTE-balanced dataset for subsequent analysis.

Identify What Predicts Real Friendships

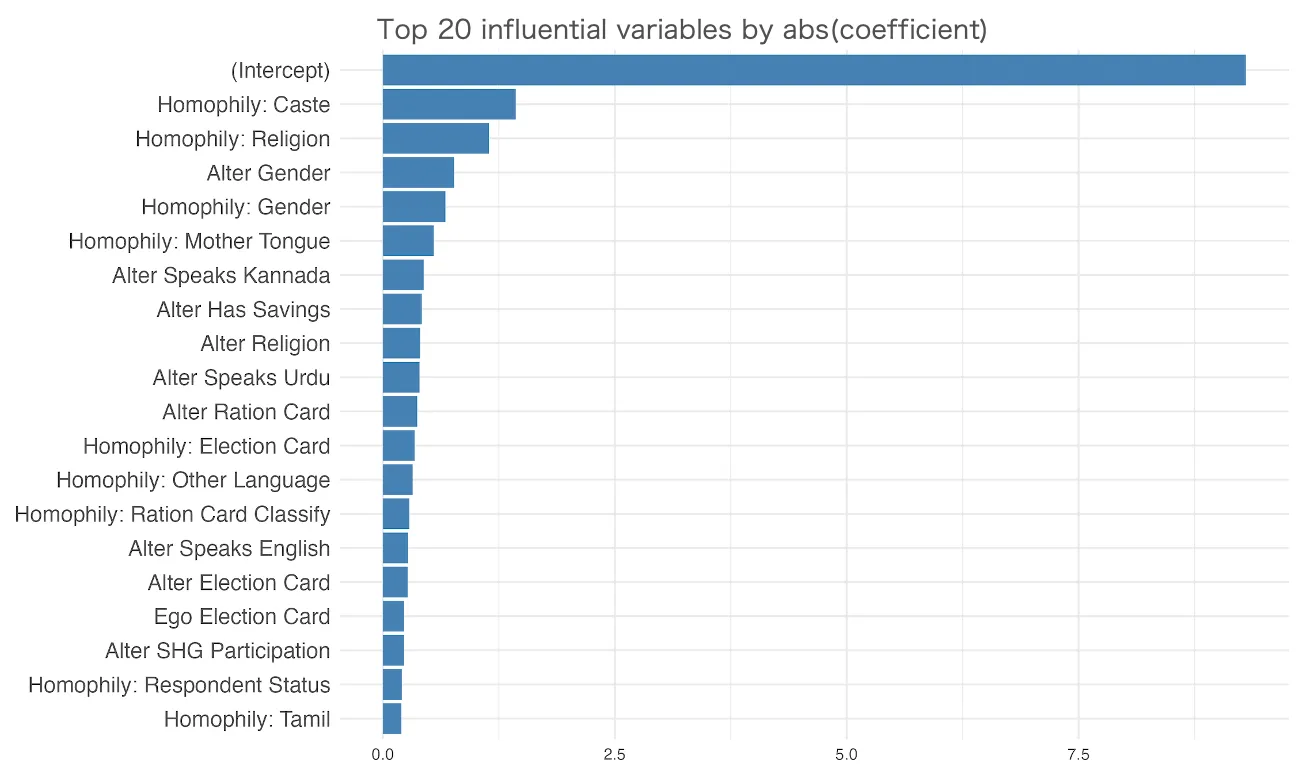

Using Lasso Logistic Regression on the real network data, I identified which attributes most strongly predict whether two people will be connected. The top predictors were caste, religion, gender, and mother tongue—reflecting the homophily principle (people tend to befriend similar others).

Histogram of abs(coef): Top demographic attributes predicting friendships in real-world data

However, notice that most of the variance in friendship formation is unexplained by demographics alone. This suggests a realistic upper bound for how well any model (including LLMs) can predict friendships based solely on these attributes.

Rank from the most influential variable to the least influential variables:

- Caste

- Religion

- Gender

- Mother

- Tongue

- If vilager have savings

- Ration card ownership

- Election card ownership

- Ration card classify

- Speak English or not

- If vilager participate SHG or not

- Status

Ask LLM Agents to Predict Friendships

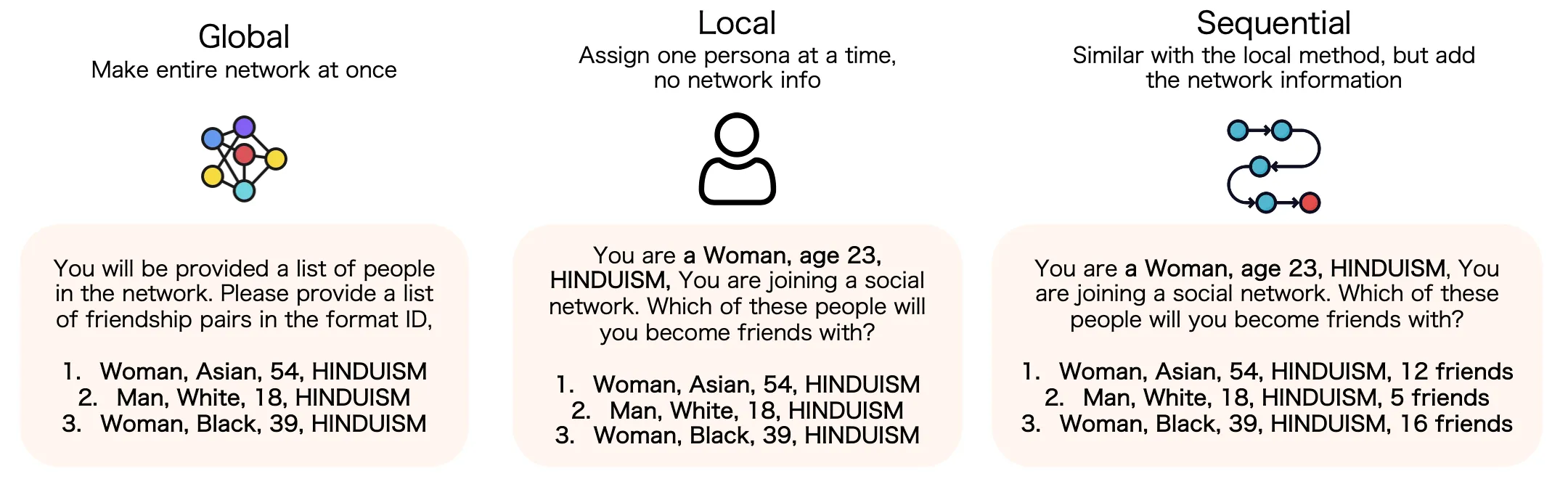

Now it comes to the core of the experiment: Can LLMs predict friendships based on these attributes? The prompt design refer methods from existing research 3, which proven to generate structurally realistic networks:

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Global | Show all 30 personas, ask AI to generate entire network at once |

| Local | Give one persona at a time, ask who they’d befriend from the others |

| Sequential | Like local, but include existing network information(from previous LLM-agent’s response) |

Three prompting methods for LLM social network generation

From previous step, we know which attributes matter for network formation.

We select one of the smallest village (village 10th) with 93 villagers to run the simulation in order to know how different attributes affect the prediction accuracy. We select the top 2, 4, 6, 8 and all 12 attributes to include in the prompts and see how prediction accuracy changes.

Findings

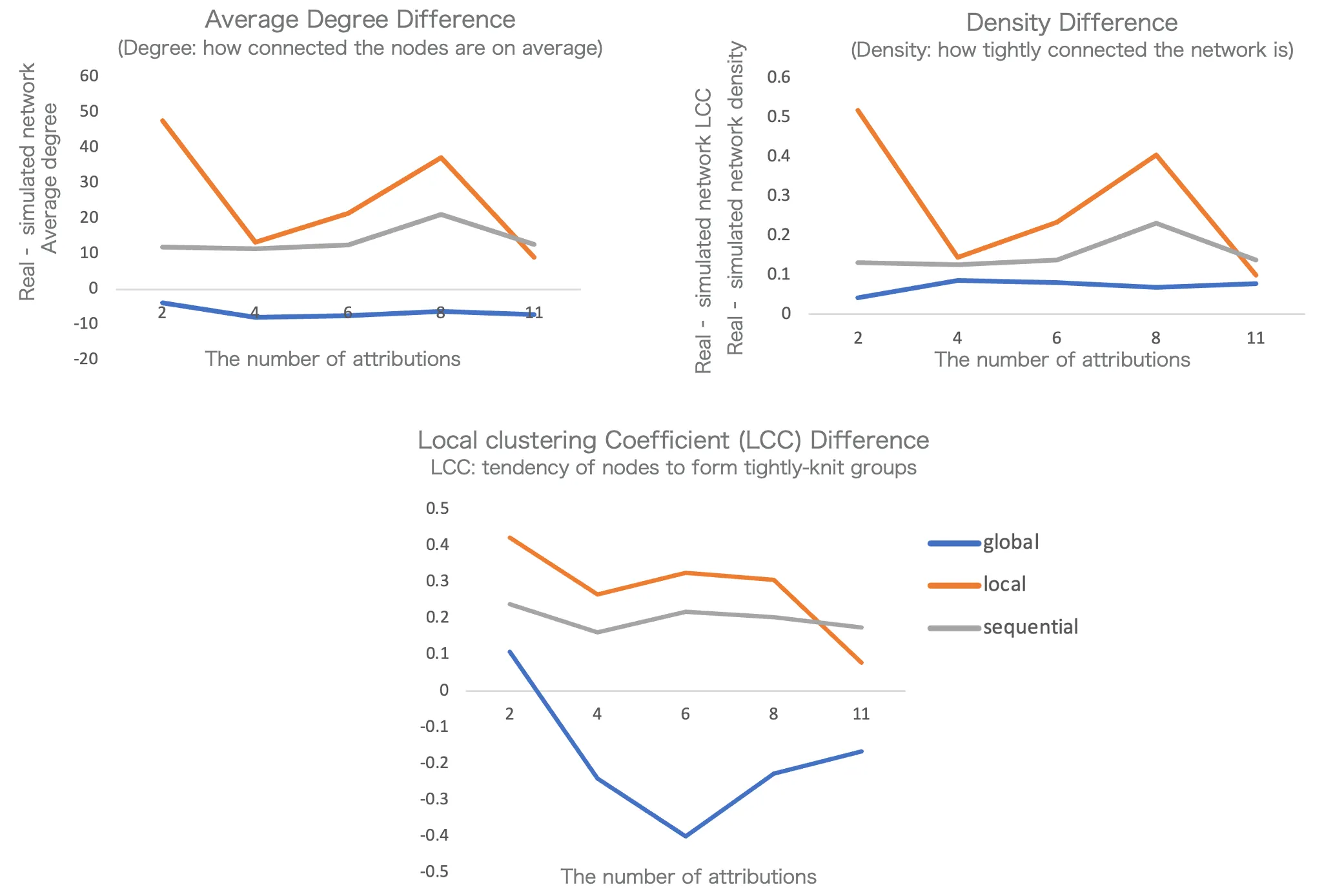

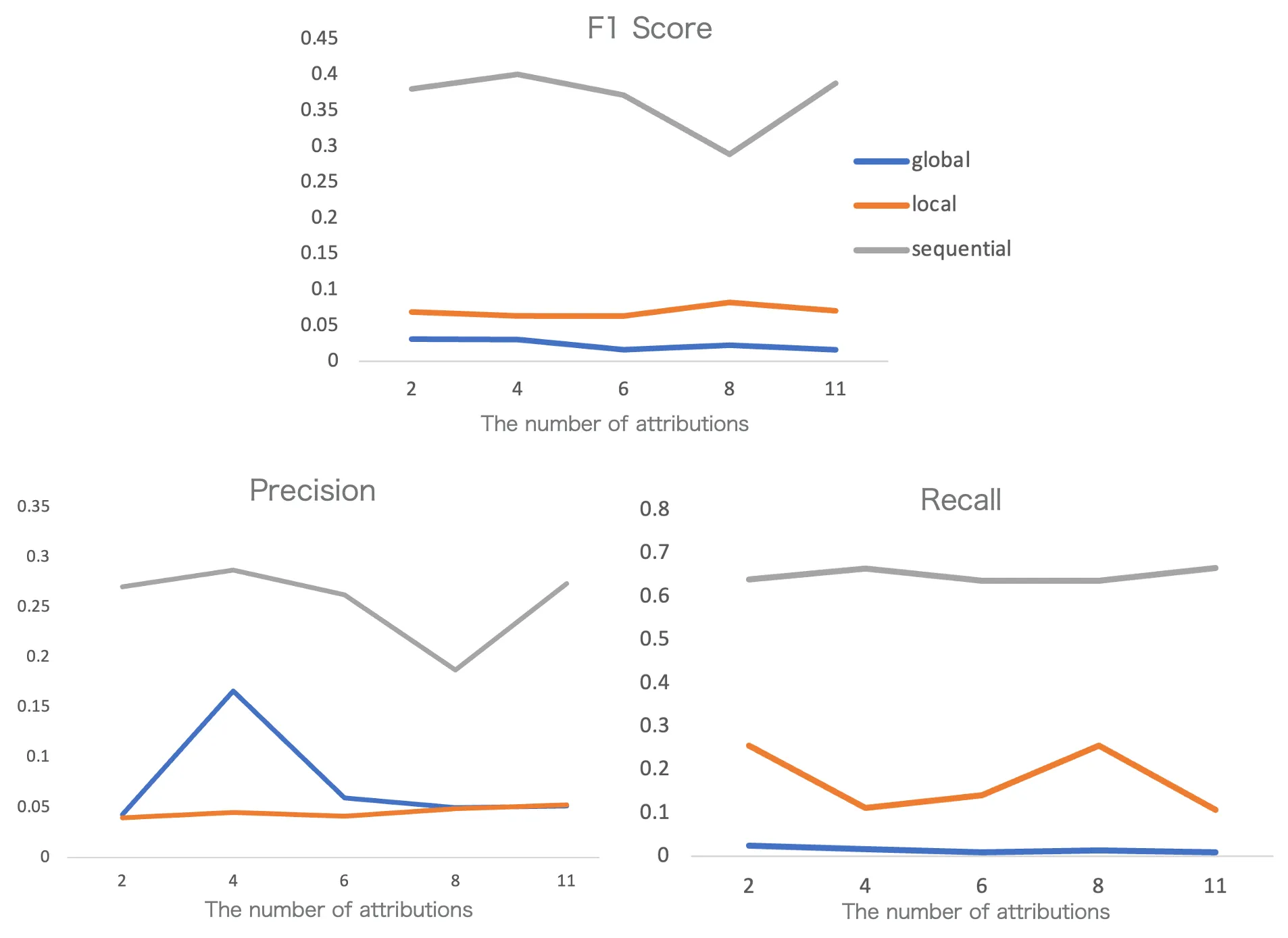

Interestingly, the performance did not improve consistently as we added more attributes. 4 attributes performed best and adding more led to diminishing returns.

Structural metrics: Global method performs best on overall network structure

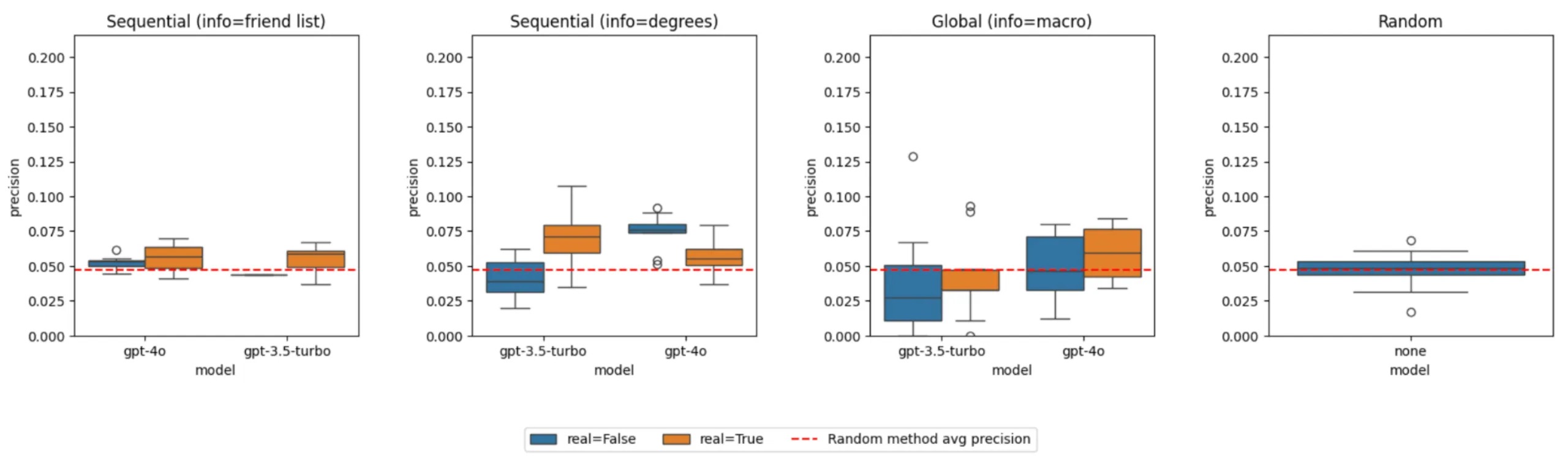

Edge-level accuracy: Sequential method leads but still shows low precision

-

More attributes didn’t help. The model perform best when there are 4 attributes, but keep adding more attributes showed no consistent improvement in prediction accuracy.

-

Structural similarity is misleading. When evaluated by traditional network metrics (density, average degree), the Global method performed best. But at the edge level, it performed poorly. This is the critical insight: a network can look statistically similar while being completely wrong about who connects to whom.

Can Real-World Information Improve Accuracy?

I tested whether providing LLMs with real network information—either micro-level (individual friend counts or lists) or macro-level (network-wide statistics)—could improve predictions.

🔍 Explore Prompts by Method

Agents join one-by-one, seeing who others are connected to

System Prompt

You are 60. backward class caste, HINDUISM, Woman, KANNADA, age 65. You are joining a social network. You will be provided a list of people in the network, where each person is described as "ID. Caste, Religion, Gender, Mothertongue, Age", followed by their current friends IDs. In your free time, whose house do you visit? Provide a list of YOUR friends in the format ID, ID, ID, etc. Do not include any other text in your response. Do not include any people who are not listed below. Do not select yourself.

User Prompt (example)

3. backward class caste, HINDUISM, Woman, KANNADA, age 28; friends with IDs 43, 22, 1 31. backward class caste, HINDUISM, Woman, KANNADA, age 70; friends with IDs 21, 33 56. backward class caste, HINDUISM, Woman, KANNADA, age 20; friends with IDs 8, 15, 42

Precision comparison across different LLM methods and information conditions

Real information helps, but only marginally. Precision improved from ~5% (random baseline) to ~8% at best. Interestingly, providing degree counts often outperformed giving complete friend lists—more information didn’t mean better predictions.

How LLMs Misunderstand Network Structure

Looking at the structural properties of generated networks revealed why:

Average degree comparison across different LLM methods and information conditions

LLMs fail in two opposite directions:

-

With friend lists → Over-prediction. GPT-4o generated networks with ~50 average connections, far exceeding the actual ~9. Detailed information triggered an “everyone knows everyone” bias.

-

With macro statistics → Under-prediction. Even when told “average degree is 8.8,” the Global method produced networks with only ~5 connections per person.

Key insight: LLMs cannot translate between micro and macro levels of network understanding. This fundamental limitation shifted my focus from optimizing accuracy to understanding how LLMs conceptualize social relationships differently.

Does Language Change AI Social Behavior?

Due to unequal distribution of language in training datasets, LLMs generally perform better in English78. Most research on multilingual prompts focuses on improving LLM performance in minority languages—but rarely examines how prompt language affects LLM behavior in social simulations.

Cross-National Dataset

I used the ISSP 2017 Social Networks survey: a dataset from 30 countries measuring social behavior like frequency of meeting friends, trust levels, and loneliness.

The ISSP 2017 Social Networks survey dataset webpage

Simulation Design

For each country, I:

- Added country context to the persona (e.g., “You are a typical adult living in Spain”) and translated prompts into corresponding local language (e.g., Spanish for Spain, Japanese for Japan)

🌍 Explore Cross-Cultural Prompts

English baseline prompt for individual agent

System Prompt

You are a typical adult. Task: • After silent reasoning, list EVERY person in the roster you would be close friends with. By "friends," we mean people you regularly interact with and trust enough to discuss personal matters or ask small favors. • Output one line of IDs separated by comma + single space: ID1, ID2, ID3, ... • Use ONLY IDs from the roster. Do NOT include your own ID. No extra text. Think step-by-step internally; reveal ONLY the final ID list. DO NOT ADD ANY ADDITIONAL WORDS

User Prompt (example)

YOUR PROFILE ID: 24 24. female, age 69, Upper secondary, In paid work ROSTER: ID, Sex, Age, Education, Working Status 2. male, age 48, Lower secondary, Retired 28. female, age 23, Lower level tertiary, In paid work 13. male, age 77, Lower level tertiary, Retired

- Generated 30 networks per country using both Local and Global methods, each network with 30 personas

- Tested with GPT-3.5-turbo and GPT-4o

Overview of Generated Networks

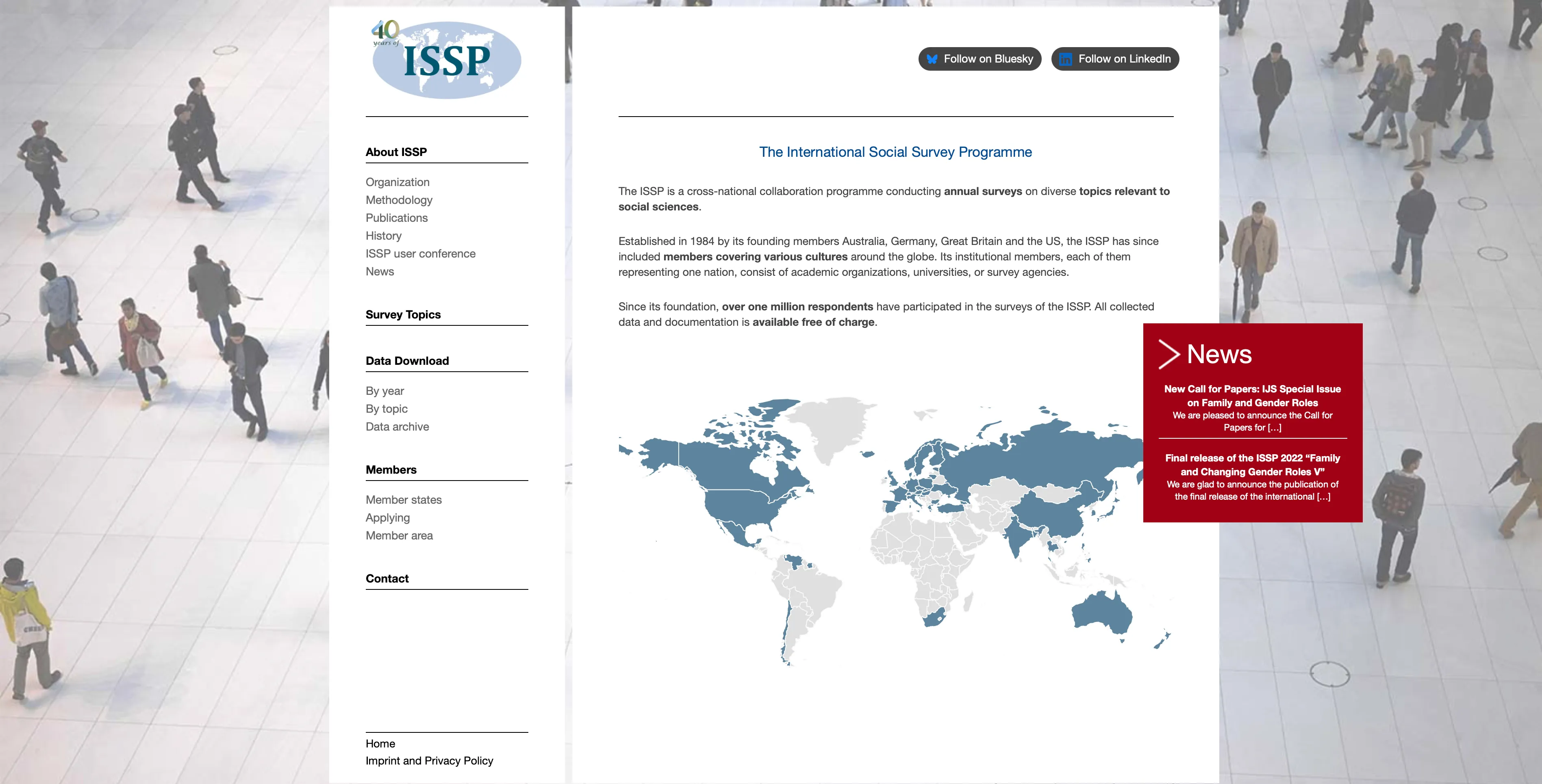

We starting from examining the most basic network property: degree distribution. The degree distribution of most of countries predicted network are similar, which follow the power law distribution similar in the real-world.

Degree distribution of LLM-generated networks across different countries

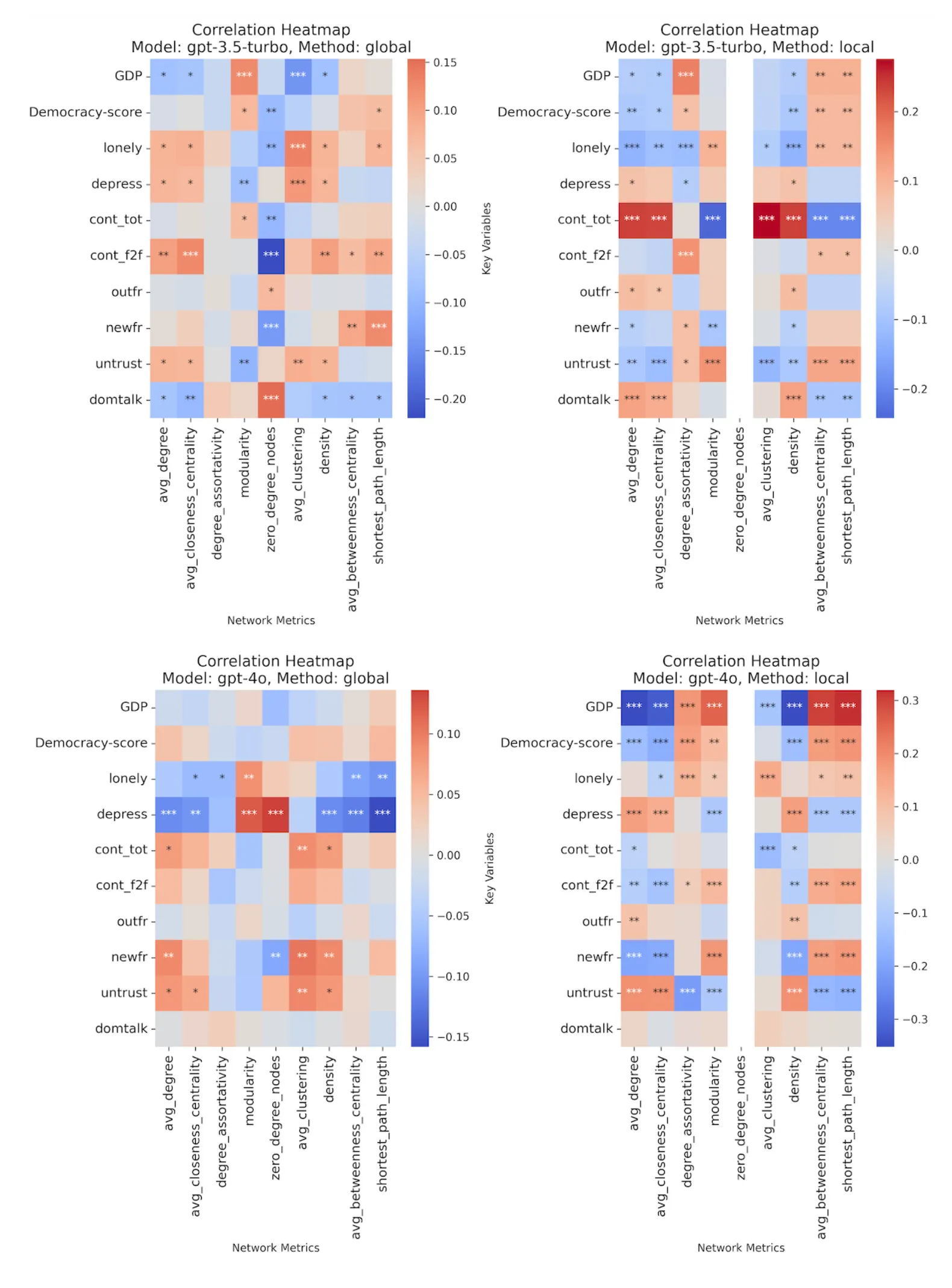

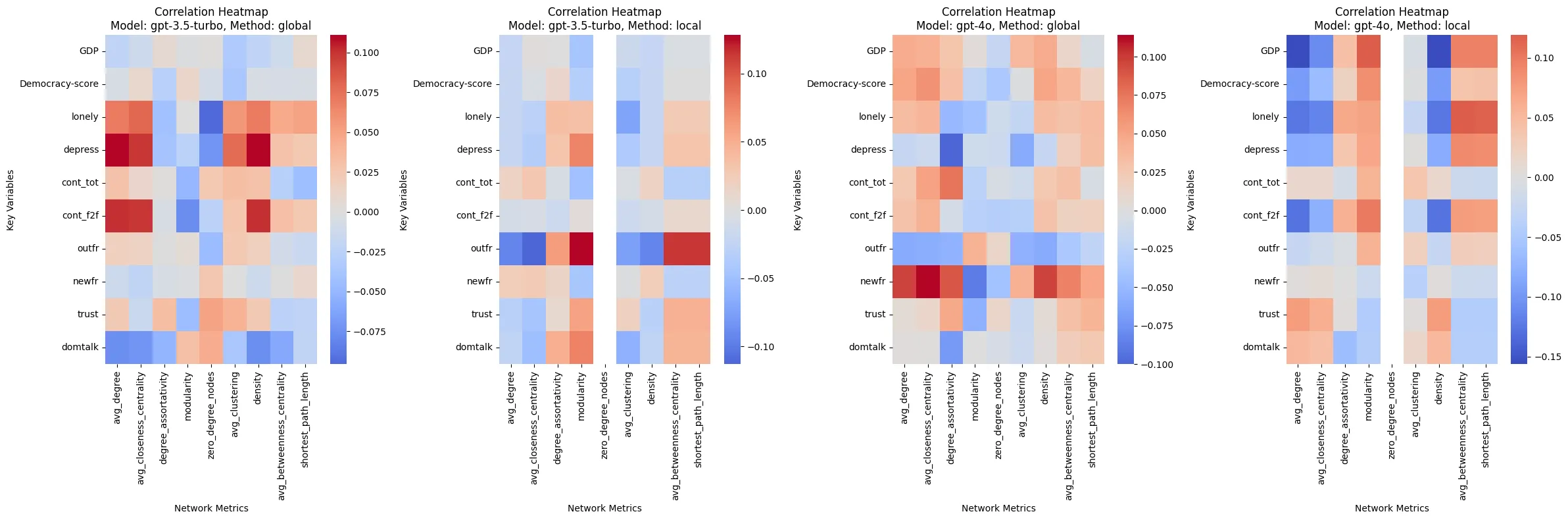

Language Context Matters

I computed correlations between:

- Real-world country-level variables (GDP, democracy score, loneliness, depression, trust, etc.)

- Network metrics from LLM simulations (average degree, clustering, density, etc.)

Correlation heatmap between LLM network metrics and real-world country variables (the missing part in zero_degree_nodes is due to no node in the generated network have zero degree)

To view variable definitions, Click me!

| Variables | Explain |

|---|---|

| cont_tot | In contact with how many people on a typical weekday |

| cont_f2f | Face-to-face contacts on a weekday |

| outfr | How often go out with friend |

| newfr | How often make new friends when going out |

| untrust | People cannot be trusted or cannot be too careful in dealing with people |

| domtalk | One person dominates conversation with friends |

| avg_degree | Average number of connections per node in the network |

| avg_closeness_centrality | Average measure of how close each node is to all other nodes |

| degree_assortativity | Tendency of nodes to connect with others of similar degree |

| modularity | Strength of division of the network into distinct communities |

| zero_degree_nodes | Number of isolated nodes with no connections |

| avg_clustering | Average probability that a node’s neighbors are also connected |

| density | Ratio of actual connections to all possible connections |

| avg_betweenness_centrality | Average measure of how often a node lies on shortest paths between others |

| shortest_path_length | Average minimum number of steps between any two nodes |

Interestingly, if we simply use english prompts for all countries, the correlations are much weaker. The maximum correlation coefficient between network matrix and country variables is around 0.1, it is about 1/3 of the correlation when using local language prompts. It suggest that language amplify the LLM’s pattern when predicted a social network, whatever it is a bias stereotype or a pattern existed in real world.

Correlation heatmap when using English prompts for all countries (much weaker than language-specific prompts)

- Prompt language affects network structure but inconsistently. For example, in GPT-3.5-turbo, higher GDP countries show lower average degree and sparser networks, while GPT-4o shows the opposite pattern.

- LLM-generated networks don’t have a stable pattern. For instance, cont_tot (weekly contact frequency) should positively correlate with avg_degree, but this only holds for GPT-3.5-turbo local and GPT-4o global. GPT-4o local shows a negative correlation, and GPT-3.5-turbo global shows no significant relationship.

- GPT-4o produces more significant correlations than GPT-3.5-turbo, but not more valid ones. Notably, GPT-4o’s generated networks correlate more strongly and consistently with country-level variables (GDP, democracy index) than with individual-level behavioral measures (e.g., cont_tot, cont_f2f). This suggests GPT-4o may rely more on stereotypical associations about “what social networks should look like in certain types of countries” rather than capturing actual individual-level variations.

When we look further into the correlations, a surprising pattern emerges: GDP and democracy index show stronger correlations with predicted network metrics, while individual-level social behavior variables (contact frequency, loneliness) which should relate to networks more directly, show weaker or inconsistent correlations.

GDP predicts friendships, but weekly contact frequency doesn't. Why?

Click to reveal

These indicators represent an outsider's view—how the world ranks and describes countries. And that's exactly what's in the training data: text that talks about countries, not the lived experience of people in them.

Click to flip back

Key Takeaways

Structural ≠ Accurate

Networks can look statistically similar while being completely wrong at the individual level

Imagined, Not Lived

The predicted network structure are more related to how countries are described from the outside than to measures of people’s lived experience within the country

Language As Amplifier

Prompt language amplifys LLM’s pattern when predicting social networks, whether it’s bias or real-world patterns

Reflection

Through this project, I realized again that there’s no such thing as “terrible data” that’s impossible to extract insights from—only the challenge of figuring out how to visualize it, find patterns, and come up with statistical tests suitable for what you have. The results also taught me that hoping LLMs can magically produce behavior that accurately captures human behavior is unrealistic. LLMs are technical products, and the outcomes of LLM-based simulations are largely shaped by how you design prompts, post-process responses, and visualize the results. There’s no magic here, only design choices and their consequences.

References

Footnotes

-

Grossmann, I., et al. (2023). AI and the transformation of social science research. Science, 380(6650), 1108–1109. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adi1778 ↩

-

Gürcan, Ö. (2024). LLM-Augmented Agent-Based Modelling for Social Simulations: Challenges and Opportunities. In Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence and Applications. IOS Press. https://doi.org/10.3233/FAIA240190 ↩

-

Chang, S., et al. (2024). LLMs generate structurally realistic social networks but overestimate political homophily. arXiv:2408.16629. http://arxiv.org/abs/2408.16629 ↩ ↩2

-

Atari, M., et al. (2023). Which Humans? PsyArXiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5b26t ↩

-

Wang, A., et al. (2024). Large language models cannot replace human participants because they cannot portray identity groups. arXiv:2402.01908. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2402.01908 ↩

-

Banerjee, A., et al. (2013). The diffusion of microfinance. Science, 341(6144), 1236498. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1236498 ↩

-

Kreutzer, J., et al. (2022). Quality at a Glance: An Audit of Web-Crawled Multilingual Datasets. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 10, 50–72. https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00447 ↩

-

Li, Z., et al. (2025). Language Ranker: A Metric for Quantifying LLM Performance Across High and Low-Resource Languages. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 39(27), 28186–28194. https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v39i27.35038 ↩